Download the notebook here!

Interactive online version:

Potential Outcomes Model

Reference: Causal Inference: The Mixtape, Chapter 4: Potential Outcomes Causal Model (pp. 119-174)

This lecture introduces the potential outcome framework for causal inference. We apply these concepts using the Online Retail Simulator to answer: What would be the effect on sales if we improved product content quality?

Part I: Theory

This section covers the theoretical foundations of the potential outcome framework as presented in Cunningham’s Causal Inference: The Mixtape, Chapter 4.

The Potential Outcome Framework

The potential outcome framework, also known as the Rubin Causal Model (RCM), provides a precise mathematical language for defining causal effects. The framework was developed by Donald Rubin in the 1970s, building on earlier work by Jerzy Neyman.

Core Definitions

For each unit \(i\) in a population, we define:

\(D_i \in \{0, 1\}\): Treatment indicator (1 if unit receives treatment, 0 otherwise)

\(Y_i^1\): Potential outcome under treatment — the outcome unit \(i\) would have if treated

\(Y_i^0\): Potential outcome under control — the outcome unit \(i\) would have if not treated

The key insight is that both potential outcomes exist conceptually for every unit, but we can only observe one of them.

The Switching Equation

The observed outcome follows the switching equation:

This equation formalizes which potential outcome we observe:

If \(D_i = 1\) (treated): we observe \(Y_i = Y_i^1\)

If \(D_i = 0\) (control): we observe \(Y_i = Y_i^0\)

The Fundamental Problem of Causal Inference

Holland (1986) articulated what he called the fundamental problem of causal inference: we cannot observe both potential outcomes for the same unit at the same time.

Consider this example:

Unit |

Treatment |

Observed |

\(Y^1\) |

\(Y^0\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

A |

Treated |

$500 |

$500 |

? |

B |

Control |

$300 |

? |

$300 |

C |

Treated |

$450 |

$450 |

? |

D |

Control |

$280 |

? |

$280 |

The question marks represent counterfactuals — outcomes that would have occurred under the alternative treatment assignment. These are fundamentally unobservable.

This is not a data limitation that can be solved with more observations or better measurement. It is a logical impossibility: the same unit cannot simultaneously exist in both treatment states.

Individual Treatment Effects

The individual treatment effect (ITE) for unit \(i\) is defined as:

This measures how much unit \(i\)’s outcome would change due to treatment.

Key insight: Because we can never observe both \(Y_i^1\) and \(Y_i^0\) for the same unit, individual treatment effects are fundamentally unidentifiable. This is why causal inference focuses on population-level parameters instead.

Population-Level Parameters

Since individual effects are unobservable, we focus on population averages:

Parameter |

Definition |

Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

ATE |

\(E[Y^1 - Y^0]\) |

Average effect across all units |

ATT |

\(E[Y^1 - Y^0 \mid D=1]\) |

Average effect among units that were treated |

ATC |

\(E[Y^1 - Y^0 \mid D=0]\) |

Average effect among units that were not treated |

When Do These Differ?

If treatment effects are homogeneous (same for everyone), then \(\text{ATE} = \text{ATT} = \text{ATC}\).

If treatment effects are heterogeneous and correlated with treatment selection, these parameters will differ. For example, if high-ability workers are more likely to get job training and benefit more from it, then \(\text{ATT} > \text{ATE}\).

The Naive Estimator and Selection Bias

The most intuitive approach to estimating causal effects is the naive estimator (also called the simple difference in means):

This compares average outcomes between treated and control groups. When does this equal the ATE?

Decomposing the Naive Estimator

We can decompose the naive estimator as follows:

The naive estimator equals the ATE only when selection bias is zero.

What Causes Selection Bias?

Selection bias occurs when treatment assignment is correlated with potential outcomes:

This happens when treated units would have had different outcomes than control units even without treatment.

Full Bias Decomposition (with Heterogeneous Effects)

When treatment effects vary across units, the full decomposition is:

Baseline bias: Treated units have different baseline outcomes

Differential treatment effect bias: Treated units have different treatment effects

Randomization: The Gold Standard

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) solve the selection bias problem by ensuring treatment is assigned independently of potential outcomes.

Independence Assumption

Under randomization:

This means potential outcomes are statistically independent of treatment assignment.

Why Randomization Works

Under independence:

Therefore:

The naive estimator becomes unbiased under randomization.

SUTVA: Stable Unit Treatment Value Assumption

The potential outcome framework relies on a critical assumption called SUTVA, which has two components:

1. No Interference

One unit’s treatment assignment does not affect another unit’s potential outcomes:

Violations:

Vaccine trials: Your vaccination protects others (herd immunity)

Classroom interventions: Tutoring one student may help their study partners

Market interventions: Promoting one product may cannibalize another

2. No Hidden Variations in Treatment

Treatment is well-defined — there is only one version of “treatment” and one version of “control”:

Violations:

Drug dosage varies across treated patients

Job training programs have different instructors

“Content optimization” could mean different things for different products

Part II: Application

We now apply the potential outcome framework to a business question using simulated data. The simulator gives us a “god’s eye view” — we observe both potential outcomes, allowing us to compute true treatment effects and validate our estimators.

[1]:

# Standard library

import inspect

# Third-party packages

from IPython.display import Code

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

# Local imports

from online_retail_simulator import simulate, load_job_results

from online_retail_simulator.enrich import enrich

from online_retail_simulator.enrich.enrichment_library import quantity_boost

from support import (

generate_quality_score,

plot_balance_check,

plot_individual_effects_distribution,

plot_randomization_comparison,

plot_sample_size_convergence,

print_bias_decomposition,

print_ite_summary,

print_naive_estimator,

)

# Set seed for reproducibility of random samples shown in output displays

np.random.seed(42)

Business Question

What would be the effect on sales if we improved product content quality?

An e-commerce company is considering investing in content optimization (better descriptions, images, etc.) for its product catalog. Before rolling this out to all products, they want to understand the causal effect of content optimization on revenue.

In our simulation:

Variable |

Notation |

Description |

|---|---|---|

Treatment |

\(D=1\) |

Product receives content optimization |

Control |

\(D=0\) |

Product keeps original content |

Outcome |

\(Y\) |

Product revenue |

Data Generation

We simulate 5,000 products with a single day of sales data. This gives us cross-sectional data: one revenue observation per product.

[2]:

!cat "config_simulation.yaml"

STORAGE:

PATH: output

RULE:

PRODUCTS:

FUNCTION: simulate_products_rule_based

PARAMS:

num_products: 5000

seed: 42

METRICS:

FUNCTION: simulate_metrics_rule_based

PARAMS:

date_start: "2024-11-15"

date_end: "2024-11-15"

sale_prob: 0.7

seed: 42

PRODUCT_DETAILS:

FUNCTION: simulate_product_details_mock

[3]:

# Run simulation

job_info = simulate("config_simulation.yaml")

results = load_job_results(job_info)

products, metrics_baseline = results["products"], results["metrics"]

print(f"Products: {len(products)}")

print(f"Metrics records: {len(metrics_baseline)}")

print(f"Date: {metrics_baseline['date'].unique()[0]}")

Products: 5000

Metrics records: 5000

Date: 2024-11-15

Treatment Effect Configuration

The simulator’s enrichment pipeline applies treatment effects. Here’s the configuration for random treatment assignment with a 50% boost to sales quantity:

[4]:

!cat "config_enrichment_random.yaml"

IMPACT:

FUNCTION: quantity_boost

PARAMS:

effect_size: 0.5

enrichment_fraction: 0.3

enrichment_start: "2024-11-15"

seed: 42

[5]:

Code(inspect.getsource(quantity_boost), language="python")

[5]:

def quantity_boost(metrics: list, **kwargs) -> tuple:

"""

Boost ordered units by a percentage for enriched products.

Args:

metrics: List of metric record dictionaries

**kwargs: Parameters including:

- effect_size: Percentage increase in ordered units (default: 0.5 for 50% boost)

- enrichment_fraction: Fraction of products to enrich (default: 0.3)

- enrichment_start: Start date of enrichment (default: "2024-11-15")

- seed: Random seed for product selection (default: 42)

- min_units: Minimum units for enriched products with zero sales (default: 1)

Returns:

Tuple of (treated_metrics, potential_outcomes_df):

- treated_metrics: List of modified metric dictionaries with treatment applied

- potential_outcomes_df: DataFrame with Y0_revenue and Y1_revenue for all products

"""

effect_size = kwargs.get("effect_size", 0.5)

enrichment_fraction = kwargs.get("enrichment_fraction", 0.3)

enrichment_start = kwargs.get("enrichment_start", "2024-11-15")

seed = kwargs.get("seed", 42)

min_units = kwargs.get("min_units", 1)

if seed is not None:

random.seed(seed)

unique_products = list(set(record["product_id"] for record in metrics))

n_enriched = int(len(unique_products) * enrichment_fraction)

enriched_product_ids = set(random.sample(unique_products, n_enriched))

treated_metrics = []

potential_outcomes = {} # {(product_id, date): {'Y0_revenue': x, 'Y1_revenue': y}}

start_date = datetime.strptime(enrichment_start, "%Y-%m-%d")

for record in metrics:

record_copy = copy.deepcopy(record)

product_id = record_copy["product_id"]

record_date_str = record_copy["date"]

record_date = datetime.strptime(record_date_str, "%Y-%m-%d")

is_enriched = product_id in enriched_product_ids

record_copy["enriched"] = is_enriched

# Calculate Y(0) - baseline revenue (no treatment)

y0_revenue = record_copy["revenue"]

# Calculate Y(1) - revenue if treated (for ALL products)

unit_price = record_copy.get("unit_price", record_copy.get("price"))

if record_date >= start_date:

original_quantity = record_copy["ordered_units"]

boosted_quantity = int(original_quantity * (1 + effect_size))

boosted_quantity = max(min_units, boosted_quantity)

y1_revenue = round(boosted_quantity * unit_price, 2)

else:

# Before treatment start, Y(1) = Y(0)

y1_revenue = y0_revenue

# Store potential outcomes for ALL products

key = (product_id, record_date_str)

potential_outcomes[key] = {"Y0_revenue": y0_revenue, "Y1_revenue": y1_revenue}

# Apply factual outcome (only for treated products)

if is_enriched and record_date >= start_date:

record_copy["ordered_units"] = boosted_quantity

record_copy["revenue"] = y1_revenue

treated_metrics.append(record_copy)

# Build potential outcomes DataFrame

potential_outcomes_df = pd.DataFrame(

[

{

"product_identifier": pid,

"date": d,

"Y0_revenue": v["Y0_revenue"],

"Y1_revenue": v["Y1_revenue"],

}

for (pid, d), v in potential_outcomes.items()

]

)

return treated_metrics, potential_outcomes_df

[6]:

# Apply random treatment using enrichment pipeline

enrich("config_enrichment_random.yaml", job_info)

results = load_job_results(job_info)

products = results["products"]

metrics_baseline = results["metrics"]

metrics_enriched = results["enriched"]

print(f"Baseline revenue: ${metrics_baseline['revenue'].sum():,.0f}")

print(f"Enriched revenue: ${metrics_enriched['revenue'].sum():,.0f}")

Baseline revenue: $272,160

Enriched revenue: $530,534

Simulator Advantage: Full Information

Unlike real data, our simulator gives us both potential outcomes for every product. This “god’s eye view” lets us:

Compute true individual treatment effects

Calculate true population parameters (ATE, ATT, ATC)

Validate whether our estimators are biased

The Fundamental Problem in Practice

First, let’s see what we would observe in real data — only one potential outcome per product:

[7]:

# What we OBSERVE in real data

fundamental_df = (

metrics_enriched[["product_identifier", "revenue", "enriched"]]

.copy()

.rename(columns={"product_identifier": "Product", "revenue": "Observed", "enriched": "Treated"})

)

# Impute potential outcomes - we only observe ONE

fundamental_df["Y0"] = np.where(~fundamental_df["Treated"], fundamental_df["Observed"], np.nan)

fundamental_df["Y1"] = np.where(fundamental_df["Treated"], fundamental_df["Observed"], np.nan)

# Show products with positive revenue for clearer illustration

fundamental_sample = fundamental_df[fundamental_df["Observed"] > 0].sample(8, random_state=42)

fundamental_sample["Treated"] = fundamental_sample["Treated"].map({True: "Yes", False: "No"})

fundamental_sample[["Product", "Treated", "Observed", "Y0", "Y1"]]

[7]:

| Product | Treated | Observed | Y0 | Y1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3151 | BHNXZP3S7L | No | 175.76 | 175.76 | NaN |

| 2402 | BF4TWWUO3C | Yes | 26.21 | NaN | 26.21 |

| 3757 | BQBHDFTZBF | Yes | 31.13 | NaN | 31.13 |

| 1515 | B8LGMQ70K8 | Yes | 72.39 | NaN | 72.39 |

| 3176 | BKKSG5VZEY | Yes | 20.22 | NaN | 20.22 |

| 1955 | B89F7J3PA1 | Yes | 63.74 | NaN | 63.74 |

| 3832 | BR44YMGCOK | No | 263.82 | 263.82 | NaN |

| 942 | BDQCHDTEQV | Yes | 1404.46 | NaN | 1404.46 |

Full Information View

Now let’s see what the simulator actually knows — both potential outcomes:

[8]:

# Load all results including potential outcomes

results = load_job_results(job_info)

potential_outcomes = results["potential_outcomes"]

# Merge with enriched metrics to get treatment indicator

full_info_df = potential_outcomes.merge(

metrics_enriched[["product_identifier", "enriched", "revenue"]],

on="product_identifier",

)

full_info_df = full_info_df.rename(

columns={

"product_identifier": "Product",

"Y0_revenue": "Y0",

"Y1_revenue": "Y1",

"enriched": "Treated",

"revenue": "Observed",

}

)

# Show sample with positive revenue

full_info_sample = full_info_df[full_info_df["Y0"] > 0].sample(8, random_state=42)

full_info_sample["Treated"] = full_info_sample["Treated"].map({True: "Yes", False: "No"})

full_info_sample[["Product", "Treated", "Observed", "Y0", "Y1"]]

[8]:

| Product | Treated | Observed | Y0 | Y1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4133 | B4N7SHDZAB | No | 99.17 | 99.17 | 99.17 |

| 3590 | B1Y21ZUSAU | No | 3697.59 | 3697.59 | 4930.12 |

| 4672 | BKS04EJ3VK | No | 43.97 | 43.97 | 43.97 |

| 2317 | BP5XZUY40Q | No | 290.55 | 290.55 | 406.77 |

| 1215 | BL1Q5FLQZM | No | 145.14 | 145.14 | 217.71 |

| 537 | BY4QJ71AS2 | No | 28.99 | 28.99 | 28.99 |

| 2338 | BGX7Y171HF | No | 382.60 | 382.60 | 573.90 |

| 2801 | BKL0CD9IJ6 | No | 746.56 | 746.56 | 746.56 |

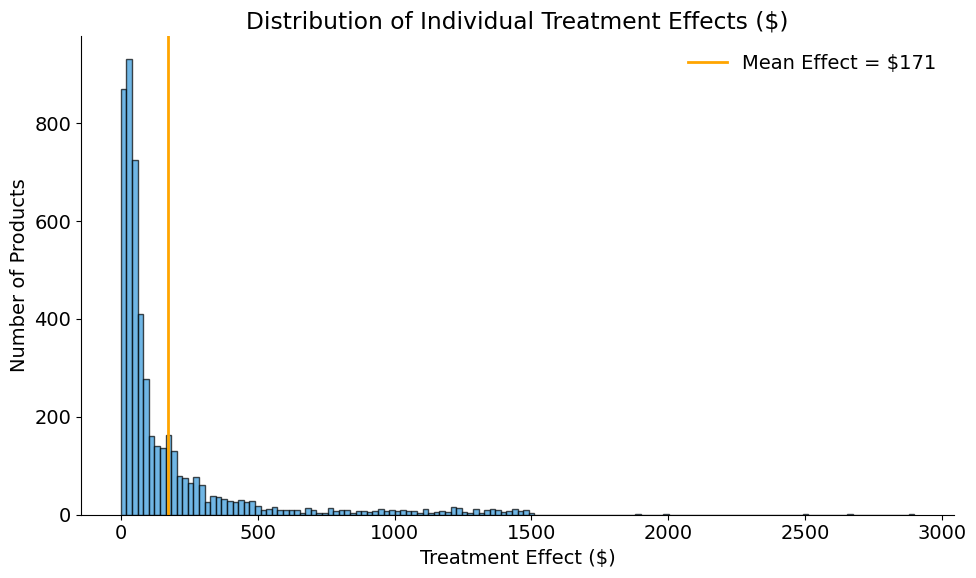

Individual Treatment Effects

Because we have both potential outcomes, we can compute true individual treatment effects:

[9]:

# Individual treatment effect: delta_i = Y^1_i - Y^0_i

full_info_df["delta"] = full_info_df["Y1"] - full_info_df["Y0"]

print_ite_summary(full_info_df["delta"])

Individual Treatment Effects:

Mean: $171.27

Std: $287.09

Min: $0.00

Max: $2,899.12

[10]:

plot_individual_effects_distribution(

full_info_df["delta"],

title="Distribution of Individual Treatment Effects ($)",

)

True Population Parameters

[11]:

# True ATE (we know both potential outcomes for all units)

ATE_true = full_info_df["delta"].mean()

print(f"True ATE: ${ATE_true:,.2f}")

True ATE: $171.27

This is the average revenue increase from content optimization.

Scenario 1: Random Treatment Assignment

Our current simulation uses random treatment assignment. Let’s verify that the naive estimator is unbiased under randomization.

[12]:

# Naive estimator under random assignment

treated = full_info_df[full_info_df["Treated"]]

control = full_info_df[~full_info_df["Treated"]]

print_naive_estimator(

treated["Observed"].mean(),

control["Observed"].mean(),

ATE_true,

title="Naive Estimator (Random Assignment)",

)

Naive Estimator (Random Assignment):

E[Y | D=1] = $229.40

E[Y | D=0] = $53.27

Naive estimate = $176.13

True ATE = $171.27

Bias = $4.86

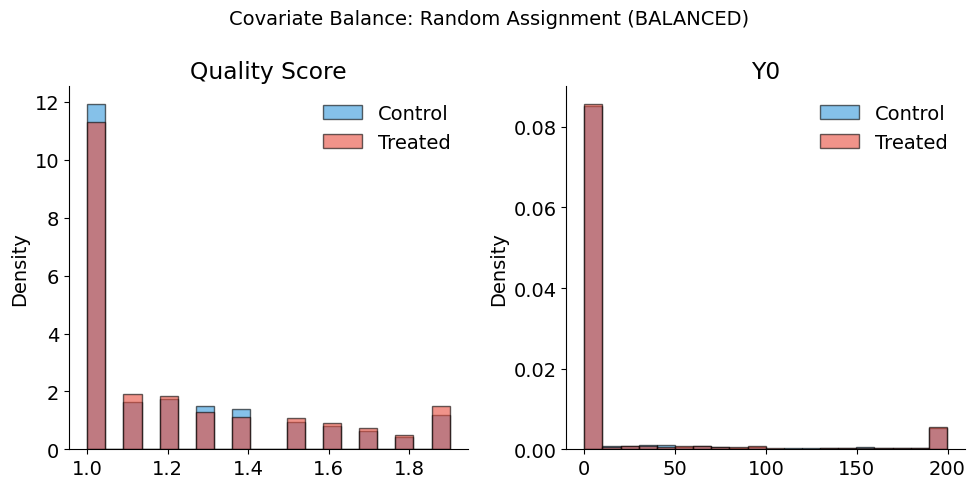

Covariate Balance Under Randomization

Let’s add a quality score (representing existing content quality) and check balance between groups:

[13]:

# Add quality score based on baseline revenue (Y0)

full_info_df["quality_score"] = generate_quality_score(full_info_df["Y0"])

print(f"Quality score range: {full_info_df['quality_score'].min():.1f} - {full_info_df['quality_score'].max():.1f}")

corr_quality_y0 = full_info_df["quality_score"].corr(full_info_df["Y0"])

print(f"Correlation(quality, Y0): {corr_quality_y0:.2f}")

Quality score range: 1.0 - 5.0

Correlation(quality, Y0): 0.46

[14]:

# Check balance under random assignment

full_info_df["D_random"] = full_info_df["Treated"].astype(int)

plot_balance_check(

full_info_df,

covariates=["quality_score", "Y0"],

treatment_col="D_random",

title="Covariate Balance: Random Assignment (BALANCED)",

)

Balance Summary (Mean by Treatment Status):

--------------------------------------------------

quality_score : Control= 1.21, Treated= 1.23, Diff= +0.02

Y0 : Control= 53.27, Treated= 57.15, Diff= +3.88

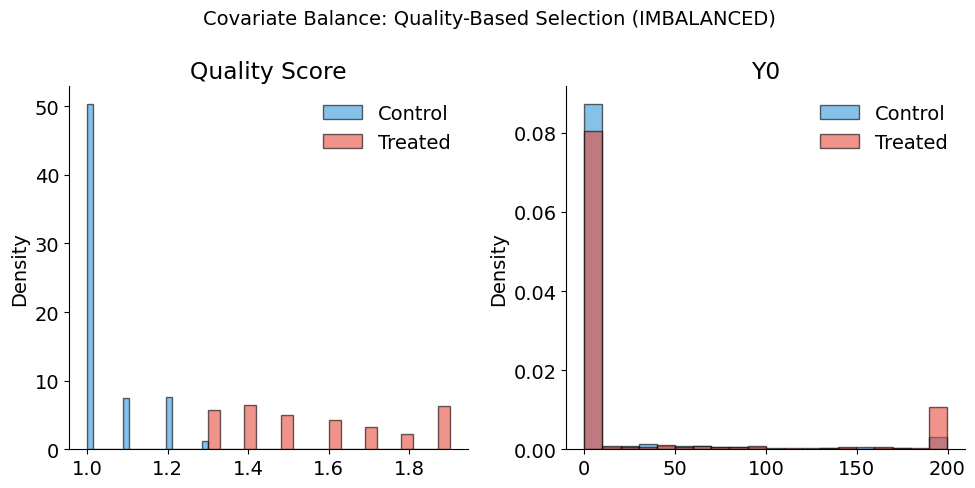

Scenario 2: Quality-Based Selection (The Real World)

In practice, businesses rarely randomize. Instead, they select products strategically — often treating high-performing products first.

Let’s simulate a realistic scenario where:

The company selects the top 30% of products by quality score for content optimization

This creates correlation between quality and treatment

[15]:

# Quality-based selection: treat TOP 30% by quality

n_treat = int(len(full_info_df) * 0.3)

treated_ids = set(full_info_df.nlargest(n_treat, "quality_score")["Product"])

full_info_df["D_biased"] = full_info_df["Product"].isin(treated_ids).astype(int)

# Observed outcome under biased selection

full_info_df["Y_biased"] = np.where(full_info_df["D_biased"] == 1, full_info_df["Y1"], full_info_df["Y0"])

print(f"Treatment selection: Top {n_treat} products by quality score")

print(f"Treated products: {full_info_df['D_biased'].sum()}")

Treatment selection: Top 1500 products by quality score

Treated products: 1500

[16]:

# Naive estimator under quality-based selection

treated_biased = full_info_df[full_info_df["D_biased"] == 1]

control_biased = full_info_df[full_info_df["D_biased"] == 0]

print_naive_estimator(

treated_biased["Y_biased"].mean(),

control_biased["Y_biased"].mean(),

ATE_true,

title="Naive Estimator (Quality-Based Selection)",

)

print("\nThe naive estimator is BIASED under non-random selection!")

Naive Estimator (Quality-Based Selection):

E[Y | D=1] = $328.04

E[Y | D=0] = $21.20

Naive estimate = $306.83

True ATE = $171.27

Bias = $135.56

The naive estimator is BIASED under non-random selection!

Bias Decomposition

Let’s verify the theoretical bias decomposition with our simulated data:

[17]:

# Baseline bias: E[Y^0 | D=1] - E[Y^0 | D=0]

baseline_treated = full_info_df[full_info_df["D_biased"] == 1]["Y0"].mean()

baseline_control = full_info_df[full_info_df["D_biased"] == 0]["Y0"].mean()

baseline_bias = baseline_treated - baseline_control

# Differential treatment effect bias: E[delta | D=1] - E[delta]

ATT = full_info_df[full_info_df["D_biased"] == 1]["delta"].mean()

differential_effect_bias = ATT - ATE_true

# Naive estimate for comparison

naive_estimate_biased = treated_biased["Y_biased"].mean() - control_biased["Y_biased"].mean()

print_bias_decomposition(baseline_bias, differential_effect_bias, naive_estimate_biased, ATE_true)

Bias Decomposition:

Baseline bias: $110.77 (treated have higher Y0)

Differential treatment effect: $24.79

────────────────────────────────────────

Total bias: $135.56

Actual bias (Naive - ATE): $135.56

Covariate Imbalance Under Biased Selection

[18]:

plot_balance_check(

full_info_df,

covariates=["quality_score", "Y0"],

treatment_col="D_biased",

title="Covariate Balance: Quality-Based Selection (IMBALANCED)",

)

Balance Summary (Mean by Treatment Status):

--------------------------------------------------

quality_score : Control= 1.04, Treated= 1.63, Diff= +0.59

Y0 : Control= 21.20, Treated= 131.97, Diff= +110.77

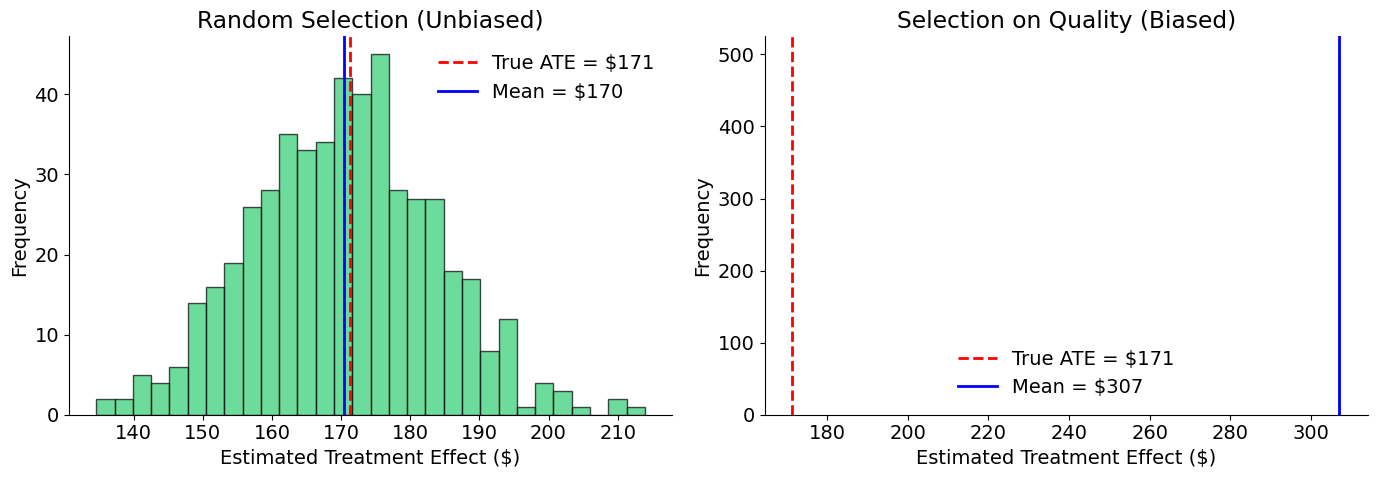

Monte Carlo Demonstration

Let’s run many simulations to see the sampling distribution of the naive estimator under random vs. biased selection:

[19]:

# Monte Carlo simulation

# 500 simulations provides stable estimates while keeping runtime reasonable (~5 seconds)

n_simulations = 500

n_treat = int(len(full_info_df) * 0.3)

random_estimates = []

biased_estimates = []

for i in range(n_simulations):

# Random selection

random_idx = np.random.choice(len(full_info_df), n_treat, replace=False)

D_random = np.zeros(len(full_info_df))

D_random[random_idx] = 1

Y_random = np.where(D_random == 1, full_info_df["Y1"], full_info_df["Y0"])

est_random = Y_random[D_random == 1].mean() - Y_random[D_random == 0].mean()

random_estimates.append(est_random)

# Quality-based selection (always picks top performers)

top_idx = full_info_df.nlargest(n_treat, "quality_score").index

D_biased = np.zeros(len(full_info_df))

D_biased[top_idx] = 1

Y_biased = np.where(D_biased == 1, full_info_df["Y1"], full_info_df["Y0"])

est_biased = Y_biased[D_biased == 1].mean() - Y_biased[D_biased == 0].mean()

biased_estimates.append(est_biased)

print(f"Random selection: Mean = ${np.mean(random_estimates):,.0f}, Std = ${np.std(random_estimates):,.0f}")

print(f"Quality selection: Mean = ${np.mean(biased_estimates):,.0f}, Std = ${np.std(biased_estimates):,.0f}")

print(f"True ATE: ${ATE_true:,.0f}")

Random selection: Mean = $170, Std = $13

Quality selection: Mean = $307, Std = $0

True ATE: $171

[20]:

plot_randomization_comparison(random_estimates, biased_estimates, ATE_true)

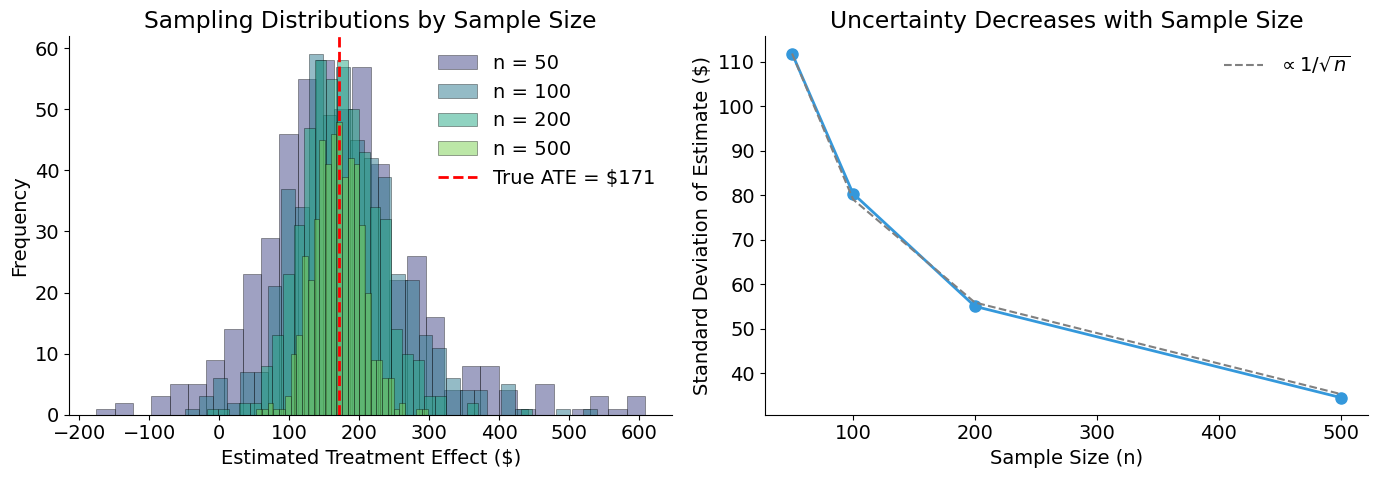

Uncertainty Decreases with Sample Size

Under random assignment, the naive estimator is unbiased — it is centered on the true ATE. However, any single estimate will differ from the true value due to sampling variability.

The standard error of the difference-in-means estimator decreases at rate \(1/\sqrt{n}\):

This means quadrupling the sample size cuts uncertainty in half.

[21]:

# Simulate at different sample sizes

sample_sizes = [50, 100, 200, 500]

n_simulations = 500

estimates_by_size = {}

for n in sample_sizes:

estimates = []

for _ in range(n_simulations):

# Random sample of n products

sample_idx = np.random.choice(len(full_info_df), n, replace=False)

sample = full_info_df.iloc[sample_idx]

# Random treatment assignment (50% treated)

n_treat = n // 2

treat_idx = np.random.choice(n, n_treat, replace=False)

D = np.zeros(n)

D[treat_idx] = 1

# Observed outcomes under random assignment

Y = np.where(D == 1, sample["Y1"].values, sample["Y0"].values)

# Naive estimate

est = Y[D == 1].mean() - Y[D == 0].mean()

estimates.append(est)

estimates_by_size[n] = estimates

# Print summary

print("Standard Deviation by Sample Size:")

for n in sample_sizes:

std = np.std(estimates_by_size[n])

print(f" n = {n:3d}: ${std:,.0f}")

Standard Deviation by Sample Size:

n = 50: $112

n = 100: $80

n = 200: $55

n = 500: $35

[22]:

plot_sample_size_convergence(sample_sizes, estimates_by_size, ATE_true)

SUTVA Considerations for E-commerce

Our simulation assumes SUTVA holds. In real e-commerce settings, we should consider:

Violation |

Example |

Implication |

|---|---|---|

Cannibalization |

Better content on Product A steals sales from Product B |

Interference between products |

Market saturation |

If ALL products are optimized, relative advantage disappears |

Effect depends on treatment prevalence |

Budget constraints |

Shoppers have fixed budgets; more on A means less on B |

Zero-sum dynamics |

Search ranking effects |

Optimized products rank higher, displacing others |

Competitive interference |

Additional resources

Athey, S. & Imbens, G. W. (2017). The econometrics of randomized experiments. In Handbook of Economic Field Experiments (Vol. 1, pp. 73-140). Elsevier.

Frölich, M. & Sperlich, S. (2019). Impact Evaluation: Treatment Effects and Causal Analysis. Cambridge University Press.

Heckman, J. J., Urzua, S. & Vytlacil, E. (2006). Understanding instrumental variables in models with essential heterogeneity. Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(3), 389-432.

Holland, P. W. (1986). Statistics and causal inference. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 81(396), 945-960.

Imbens, G. W. (2020). Potential outcome and directed acyclic graph approaches to causality: Relevance for empirical practice in economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 58(4), 1129-1179.

Imbens, G. W. & Rubin, D. B. (2015). Causal Inference in Statistics, Social, and Biomedical Sciences. Cambridge University Press.

Rosenbaum, P. R. (2002). Overt bias in observational studies. In Observational Studies (pp. 71-104). Springer.