Download the notebook here!

Interactive online version:

Directed Acyclic Graphs

Reference: Causal Inference: The Mixtape, Chapter 3: Directed Acyclic Graphs (pp. 67-117)

This lecture introduces directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) as a tool for reasoning about causal relationships. We apply these concepts using the Online Retail Simulator to answer: Why does our naive analysis suggest content optimization hurts sales?

Part I: Theory

This section covers the theoretical foundations of directed acyclic graphs as presented in Cunningham’s Causal Inference: The Mixtape, Chapter 3.

[1]:

# Standard library

import inspect

# Third-party packages

from IPython.display import Code

# Local imports

from support import draw_police_force_example, simulate_police_force_data

1. Introduction to DAG Notation

A directed acyclic graph (DAG) is a visual representation of causal relationships between variables.

Core Components

Element |

Representation |

Meaning |

|---|---|---|

Node |

Circle |

A random variable |

Arrow |

Directed edge (→) |

Direct causal effect |

Path |

Sequence of edges |

Connection between variables |

Key Properties

Directed: Arrows point in one direction (cause → effect)

Acyclic: No variable can cause itself (no loops)

Causality flows forward: Time moves in the direction of arrows

What DAGs Encode

DAGs encode qualitative causal knowledge:

What IS happening: drawn arrows

What is NOT happening: missing arrows (equally important!)

A missing arrow from A to B claims that A does not directly cause B.

Simple DAG: Treatment → Outcome

2. Paths: Direct and Backdoor

A path is any sequence of edges connecting two nodes, regardless of arrow direction.

Types of Paths

Path Type |

Direction |

Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

Direct/Causal |

D → … → Y |

The causal effect we want |

Backdoor |

D ← … → Y |

Spurious correlation (bias!) |

The Backdoor Problem

Backdoor paths create spurious correlations between D and Y:

They make D and Y appear related even without a causal effect

This is the graphical representation of selection bias

Path Analysis

Path |

Type |

|---|---|

D → Y |

Direct causal path (what we want to estimate) |

D ← X → Y |

Backdoor path (creates bias) |

3. Confounders

A confounder is a variable that:

Causes the treatment (D)

Causes the outcome (Y)

Is NOT on the causal path from D to Y

Observed vs. Unobserved

Type |

In DAG |

Implication |

|---|---|---|

Observed |

Solid circle |

Can condition on it |

Unobserved |

Dashed circle |

Cannot directly control |

Classic Example: Education and Earnings

Consider estimating the return to education:

Treatment: Years of education

Outcome: Earnings

Confounders: Ability, family background, motivation

People with higher ability tend to:

Get more education (ability → education)

Earn more regardless of education (ability → earnings)

This creates a backdoor path that inflates naive estimates of education’s effect.

4. Colliders and Collider Bias

A collider is a variable where two arrows point INTO it:

Key Insight About Colliders

Colliders have a special property: they naturally BLOCK paths!

Situation |

Path Status |

|---|---|

Leave collider alone |

Path is CLOSED (blocked) |

Condition on collider |

Path is OPENED (creates bias!) |

Why Conditioning Opens Colliders

Conditioning on a collider makes its causes appear correlated, even if they’re independent in the population.

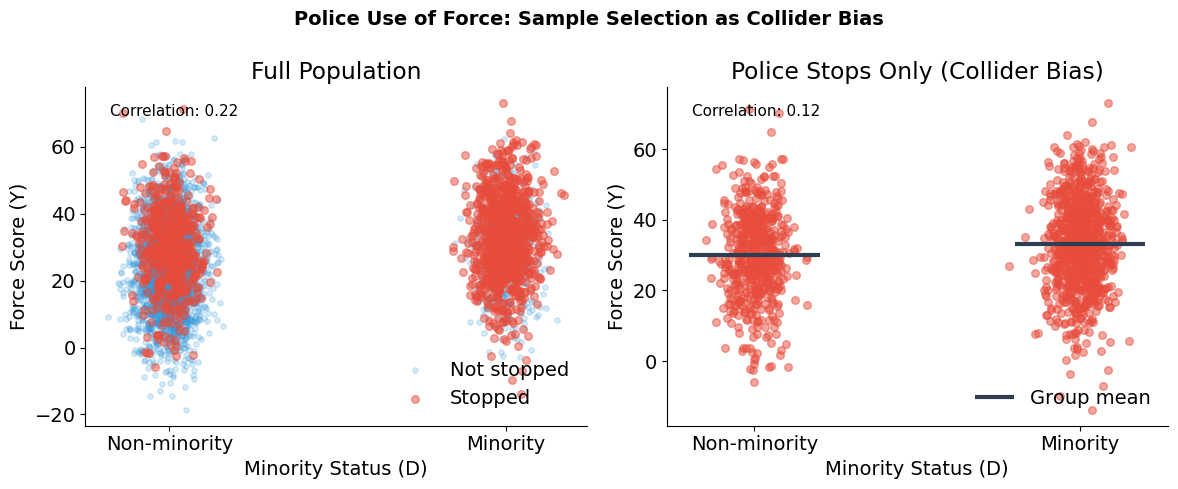

Police Use of Force: Sample Selection as a Collider

Consider studying whether police use more force against minorities:

D (Treatment): Minority status

Y (Outcome): Use of force

M (Collider): Police stop (sample selection)

U (Unobserved): Suspicion/perceived threat

The selection problem:

Minorities are more likely to be stopped (D → M)

Suspicion affects both stops and force (U → M, U → Y)

Administrative data only includes stopped individuals

Why this attenuates discrimination estimates:

Among stopped individuals (M = 1), non-minorities (D = 0) who got stopped probably had high suspicion (U)—that’s why they were stopped. Minorities (D = 1) who got stopped could have low or high suspicion, since they face higher stop rates regardless. So within the stopped sample, non-minorities are disproportionately high-suspicion, which correlates with more force (Y). This narrows the apparent gap between groups, masking the true discrimination effect (D → Y).

Simulation Setup

Why Show the Simulation Code?

In causal inference, we face a fundamental challenge: we can never directly observe causal effects in real data. When we analyze observational data, we don’t know the true causal structure—we can only make assumptions and hope our methods recover something meaningful. Simulation flips this around. By constructing data with a known causal structure, we create a laboratory where we can verify whether our intuitions and methods actually work. In the code below, we explicitly encoded that minorities face discrimination and that suspicion affects both stops and force. Because we built these relationships ourselves, we know the ground truth. This lets us see—not just theorize—how conditioning on a collider distorts our estimates. Throughout this course, simulation serves as our proving ground: if a method can’t recover known effects in simulated data, we shouldn’t trust it with real data where the stakes are higher and the truth is hidden.

The following function generates synthetic data with the collider structure described above:

[2]:

Code(inspect.getsource(simulate_police_force_data), language="python")

[2]:

def simulate_police_force_data(n_population=5000, discrimination_effect=0.3, seed=42):

"""

Simulate police stop data with collider bias structure.

The DAG structure:

Minority (D) → Stop (M) ← Suspicion (U)

Minority (D) → Force (Y)

Suspicion (U) → Force (Y)

Where Stop (M) is the collider that creates sample selection bias.

Parameters

----------

n_population : int

Size of the simulated population.

discrimination_effect : float

True causal effect of minority status on force (0 = no discrimination).

seed : int

Random seed for reproducibility.

Returns

-------

pandas.DataFrame

DataFrame with columns:

- minority: minority status (0 or 1)

- suspicion: suspicion scores

- is_stopped: boolean stop status

- force_score: force scores

"""

rng = np.random.default_rng(seed)

# Minority status (binary treatment)

minority = rng.choice([0, 1], size=n_population, p=[0.7, 0.3])

# Suspicion/perceived threat (unobserved confounder)

suspicion = rng.normal(50, 15, n_population)

# Stop probability depends on minority status AND suspicion

# Minorities are more likely to be stopped (D → M)

# Higher suspicion leads to more stops (U → M)

stop_score = (

0.3 * suspicion # Suspicion affects stops

+ 15 * minority # Minorities more likely stopped

+ rng.normal(0, 10, n_population)

)

is_stopped = stop_score > np.percentile(stop_score, 70)

# Force depends on suspicion and minority status

# True discrimination effect is the parameter

force_score = (

0.5 * suspicion # Higher suspicion → more force (U → Y)

+ discrimination_effect * 20 * minority # True discrimination (D → Y)

+ rng.normal(0, 10, n_population)

)

return pd.DataFrame(

{

"minority": minority,

"suspicion": suspicion,

"is_stopped": is_stopped,

"force_score": force_score,

}

)

[3]:

# Simulate population data

police_data = simulate_police_force_data(n_population=5000, discrimination_effect=0.3, seed=42)

police_data

[3]:

| minority | suspicion | is_stopped | force_score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 33.516132 | True | 13.429162 |

| 1 | 0 | 41.880285 | True | 20.398594 |

| 2 | 1 | 54.080017 | True | 29.253445 |

| 3 | 0 | 40.575200 | False | 28.486508 |

| 4 | 0 | 45.824503 | False | 31.391469 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 4995 | 0 | 62.382881 | False | 21.783496 |

| 4996 | 0 | 23.108498 | False | 13.325042 |

| 4997 | 0 | 34.363115 | False | 30.535183 |

| 4998 | 0 | 19.034540 | False | 13.382449 |

| 4999 | 0 | 36.538923 | False | 14.671546 |

5000 rows × 4 columns

[4]:

# Visualize collider bias

draw_police_force_example(police_data)

Collider Bias in Action

True discrimination effect: 30% increase in force for minorities

Sample |

Correlation (Minority ↔ Force) |

|---|---|

Full population |

r = 0.22 |

Stopped individuals only |

r = 0.12 |

This is collider bias: conditioning on Stop (which depends on both Minority and Suspicion) creates a spurious association. The administrative data only includes stopped individuals, so naive analysis of police records may produce misleading estimates of discrimination.

5. The Backdoor Criterion

The backdoor criterion provides a systematic way to identify what variables to condition on.

Definition

A set of variables \(Z\) satisfies the backdoor criterion relative to \((D, Y)\) if:

No variable in \(Z\) is a descendant of \(D\)

\(Z\) blocks every backdoor path from \(D\) to \(Y\)

How to Block Paths

Node Type |

To Block |

To Open |

|---|---|---|

Non-collider |

Condition on it |

Leave alone |

Collider |

Leave alone |

Condition on it |

Important Implications

Not all controls are good controls: Conditioning on a collider creates bias

Minimal sufficiency: You don’t need to condition on everything—just enough to block backdoors

Multiple solutions: Often several valid conditioning sets exist

6. Choosing the Right Estimand

The backdoor criterion tells us how to block spurious paths. But DAGs also help us reason about a subtler question: which causal effect do we actually want to estimate?

Sometimes a variable is neither a confounder nor a collider—it’s a mediator on the causal path. Whether to condition on it depends on the research question, not on removing bias.

Example: Discrimination in Hiring

Consider studying gender discrimination in wages:

Gender → Occupation (women steered to lower-paying jobs)

Gender → Wages (direct discrimination)

Occupation → Wages

Question: Should we control for occupation?

Answer: It depends on what effect we want to measure!

Total effect: Don’t control (captures both direct and indirect discrimination)

Direct effect: Control for occupation (discrimination within same job)

Part II: Application

We now apply DAG concepts to diagnose and solve a confounding problem using simulated data.

[5]:

# Third-party packages

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

# Local imports

from online_retail_simulator import simulate, load_job_results

from support import (

apply_confounded_treatment,

create_quality_score,

plot_confounding_scatter,

plot_dag_application,

)

# Fix seed for reproducibility so that all results in this notebook are deterministic

np.random.seed(42)

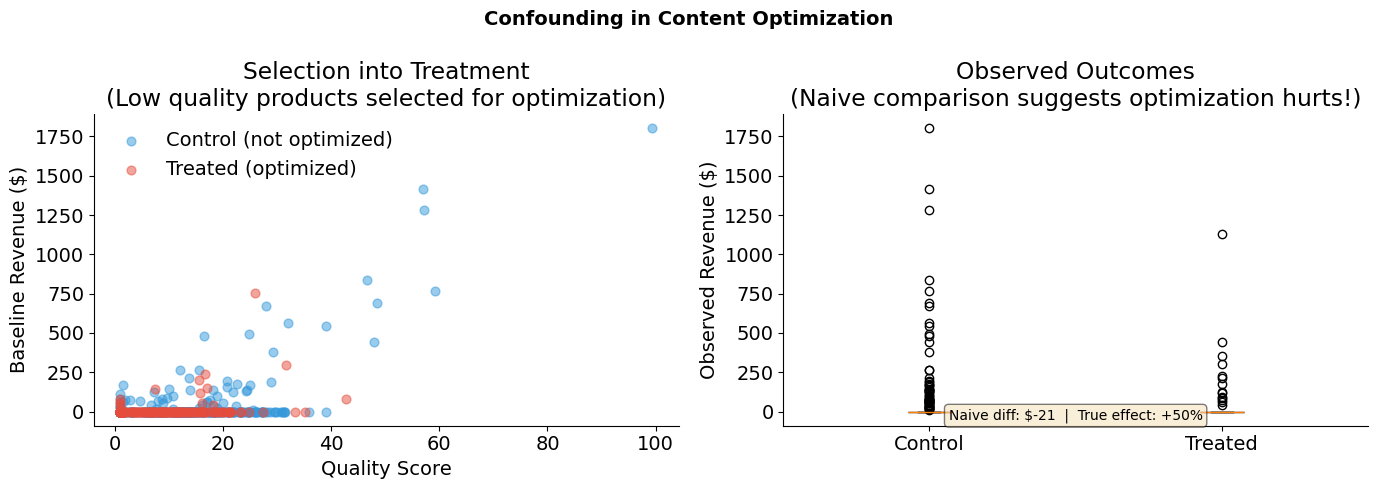

1. Business Context: The Content Optimization Paradox

An e-commerce company ran a content optimization program for some of its products. When they analyze the results, they find something puzzling:

Products that received content optimization tend to have LOWER sales than those that didn’t.

The content team is confused. Did their optimization work actually hurt sales?

The Underlying Reality

What’s actually happening:

Struggling products (low quality) were selected for content optimization

Strong products (high quality) sell well without optimization

Content optimization does increase sales (true causal effect is positive)

But the confounding from product quality creates a negative spurious correlation that overwhelms the positive causal effect. This is exactly the scenario we explored in Lecture 01—but now we’ll use DAGs to understand and solve it.

2. Drawing the DAG

Let’s represent this situation graphically:

Quality (

Q): Product quality/strength (unobserved)Optimization (

D): Content optimization treatmentSales (

Y): Revenue

Relationships:

Quality → Sales (+): Better products sell more

Quality → Optimization (−): Struggling products get optimized first

Optimization → Sales (+): Optimization increases sales (TRUE causal effect)

Path Analysis

Path |

Type |

Effect |

|---|---|---|

Optimization → Sales |

Direct (causal) |

True causal effect (+50% revenue boost) |

Optimization ← Quality → Sales |

Backdoor |

Creates negative bias (quality confounding) |

3. Generating Data with the Online Retail Simulator

We use the Online Retail Simulator to generate realistic e-commerce data. The simulation configuration is defined in "config_simulation.yaml". This gives us products with baseline sales metrics that we can then use to demonstrate confounding.

Data Generation Process

Simulate baseline data: Generate products and their sales metrics

Create quality score: Derive a quality measure from baseline revenue (the confounder)

Apply confounded treatment: Assign content optimization based on quality (not randomly!)

Calculate outcomes: Apply the true treatment effect to get observed sales

[6]:

# Step 1: Generate baseline data using the simulator

! cat "config_simulation.yaml"

STORAGE:

PATH: output

RULE:

PRODUCTS:

FUNCTION: simulate_products_rule_based

PARAMS:

num_products: 500

seed: 42

METRICS:

FUNCTION: simulate_metrics_rule_based

PARAMS:

date_start: "2024-11-15"

date_end: "2024-11-15"

sale_prob: 0.7

seed: 42

PRODUCT_DETAILS:

FUNCTION: simulate_product_details_mock

[7]:

# Run simulation

job_info = simulate("config_simulation.yaml")

[8]:

# Load simulation results

metrics = load_job_results(job_info)["metrics"]

print(f"Metrics records: {len(metrics)}")

Metrics records: 500

Creating the Confounded Treatment Assignment

Now we create the confounding structure:

Quality score: Derived from baseline revenue (high revenue → high quality)

Treatment assignment: Low quality products are more likely to be selected for optimization

This mimics a realistic business scenario where struggling products get prioritized for improvement.

[9]:

# Step 2: Create quality score from baseline revenue

quality_df = create_quality_score(metrics, seed=42)

# Step 3: Apply confounded treatment assignment

# Low quality products more likely to be optimized (negative quality_effect)

TRUE_EFFECT = 0.5 # 50% revenue boost from optimization

QUALITY_EFFECT = -0.05 # Negative: low quality products are more likely to be treated

confounded_products = apply_confounded_treatment(

quality_df,

treatment_fraction=0.3,

quality_effect=QUALITY_EFFECT,

true_effect=TRUE_EFFECT,

seed=42,

)

print(f"Total products: {len(confounded_products)}")

print(f"Optimized products: {confounded_products['D'].sum()} ({confounded_products['D'].mean():.1%})")

print(f"\nQuality score by treatment status:")

print(f" Control (not optimized): {confounded_products[confounded_products['D'] == 0]['quality_score'].mean():.1f}")

print(f" Treated (optimized): {confounded_products[confounded_products['D'] == 1]['quality_score'].mean():.1f}")

print(f"\n-> Treated products have LOWER quality on average (confounding!)")

Total products: 500

Optimized products: 157 (31.4%)

Quality score by treatment status:

Control (not optimized): 13.3

Treated (optimized): 9.8

-> Treated products have LOWER quality on average (confounding!)

[10]:

# Visualize the confounding structure

plot_confounding_scatter(confounded_products, title="Confounding in Content Optimization")

4. What Does Naive Analysis Tell Us?

Let’s start with what a naive analyst might do: compare average sales between optimized and non-optimized products.

[11]:

# Naive comparison: difference in means

treated = confounded_products[confounded_products["D"] == 1]

control = confounded_products[confounded_products["D"] == 0]

naive_estimate = treated["Y_observed"].mean() - control["Y_observed"].mean()

print("Naive Comparison: Optimized vs. Non-Optimized Products")

print("=" * 55)

print(f"Mean revenue (optimized): ${treated['Y_observed'].mean():,.2f}")

print(f"Mean revenue (not optimized): ${control['Y_observed'].mean():,.2f}")

print(f"Naive estimate: ${naive_estimate:,.2f}")

print(f"\nTrue effect: +{TRUE_EFFECT:.0%} revenue boost")

print(f"\n-> The naive estimate suggests optimization HURTS sales!")

Naive Comparison: Optimized vs. Non-Optimized Products

=======================================================

Mean revenue (optimized): $21.89

Mean revenue (not optimized): $42.67

Naive estimate: $-20.78

True effect: +50% revenue boost

-> The naive estimate suggests optimization HURTS sales!

5. How Do We Apply the Backdoor Criterion?

Step 1: List all paths from Optimization to Sales

Optimization → Sales (direct, causal)

Optimization ← Quality → Sales (backdoor, non-causal)

Step 2: Identify which paths are open/closed

Path 1: Always open (it’s causal)

Path 2: Open because Quality is a non-collider on this path

Step 3: Find conditioning set to block backdoors

To block the backdoor path Optimization ← Quality → Sales:

Condition on Quality

This satisfies the backdoor criterion:

Quality is not a descendant of Optimization

Conditioning on Quality blocks the backdoor path

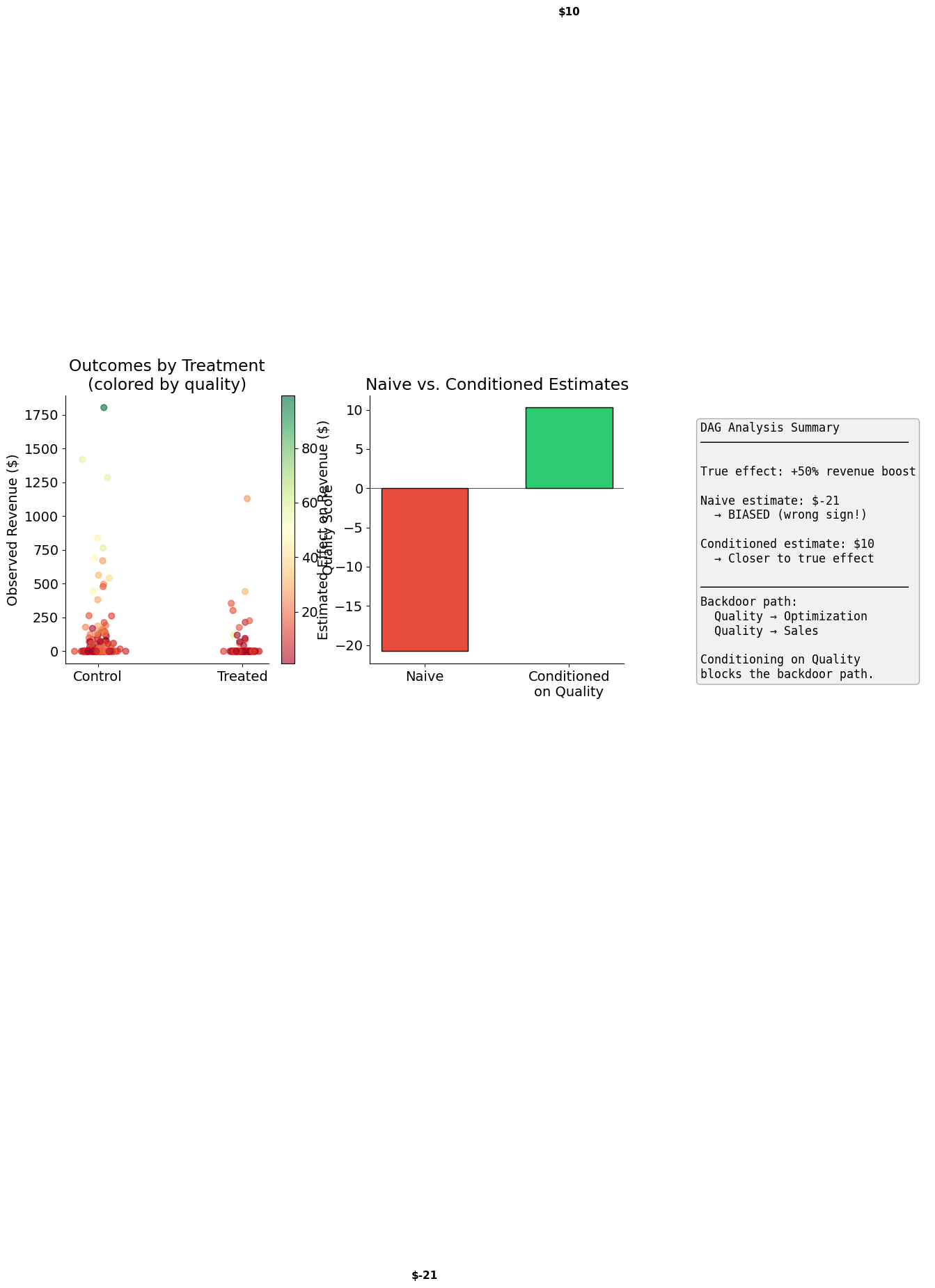

6. How Do We Recover the Causal Effect?

Now we condition on quality to close the backdoor path. We use regression to estimate the effect while controlling for the confounder.

[12]:

# Naive regression: Sales ~ Optimization (ignoring quality)

naive_results = smf.ols("Y_observed ~ D", data=confounded_products).fit()

# Conditioned regression: Sales ~ Optimization + Quality

conditioned_results = smf.ols("Y_observed ~ D + quality_score", data=confounded_products).fit()

print("Naive Regression: Y ~ D")

print("=" * 50)

print(naive_results.summary().tables[1])

print("\n\nConditioned Regression: Y ~ D + Quality")

print("=" * 50)

print(conditioned_results.summary().tables[1])

print(f"\nNaive estimate: ${naive_results.params['D']:,.2f}")

print(f"Conditioned estimate: ${conditioned_results.params['D']:,.2f}")

print(f"True effect: +{TRUE_EFFECT:.0%} boost")

print(f"\n-> Conditioning on quality recovers the POSITIVE effect!")

Naive Regression: Y ~ D

==================================================

==============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Intercept 42.6719 8.493 5.024 0.000 25.986 59.358

D -20.7801 15.156 -1.371 0.171 -50.558 8.998

==============================================================================

Conditioned Regression: Y ~ D + Quality

==================================================

=================================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Intercept -74.6617 10.166 -7.344 0.000 -94.636 -54.688

D 10.2765 12.536 0.820 0.413 -14.353 34.907

quality_score 8.8447 0.560 15.790 0.000 7.744 9.945

=================================================================================

Naive estimate: $-20.78

Conditioned estimate: $10.28

True effect: +50% boost

-> Conditioning on quality recovers the POSITIVE effect!

[13]:

# Visual summary

plot_dag_application(

confounded_products,

naive_effect=naive_results.params["D"],

conditioned_effect=conditioned_results.params["D"],

true_effect=TRUE_EFFECT,

)

/home/runner/work/courses-business-decisions/courses-business-decisions/docs/source/measure-impact/02-directed-acyclic-graphs/support.py:406: UserWarning: Tight layout not applied. The bottom and top margins cannot be made large enough to accommodate all Axes decorations.

plt.tight_layout()

[14]:

# Final summary

print("\n" + "=" * 60)

print("SUMMARY: Content Optimization Effect Estimates")

print("=" * 60)

print(f"True causal effect: +{TRUE_EFFECT:.0%} revenue boost")

print(f"\nNaive (ignoring quality): ${naive_results.params['D']:,.2f} ← WRONG SIGN!")

print(f"Conditioned on quality (correct): ${conditioned_results.params['D']:,.2f} ← POSITIVE!")

print("=" * 60)

============================================================

SUMMARY: Content Optimization Effect Estimates

============================================================

True causal effect: +50% revenue boost

Naive (ignoring quality): $-20.78 ← WRONG SIGN!

Conditioned on quality (correct): $10.28 ← POSITIVE!

============================================================

Additional resources

Bellemare, M. & Bloem, J. (2020). The paper of how: Estimating treatment effects using the front-door criterion. Working Paper.

Hünermund, P. & Bareinboim, E. (2019). Causal inference and data-fusion in econometrics. arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.09104.

Imbens, G. W. (2020). Potential outcome and directed acyclic graph approaches to causality: Relevance for empirical practice in economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 58(4), 1129-1179.

Manski, C. F. (1995). Identification Problems in the Social Sciences. Harvard University Press.

Morgan, S. L. & Winship, C. (2014). Counterfactuals and Causal Inference. Cambridge University Press.

Pearl, J. (2009a). Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Pearl, J. (2009b). Causal inference in statistics: An overview. Statistics Surveys, 3, 96-146.

Pearl, J. (2012). The do-calculus revisited. Proceedings of the 28th Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence.

Peters, J., Janzing, D. & Schölkopf, B. (2017). Elements of Causal Inference: Foundations and Learning Algorithms. MIT Press.